Introduction

An information security policy is a fundamental element of protecting information assets. It would not be an exaggeration to say that an effective information security framework starts and finishes with a well-defined and well written policy. Yet, the tradecraft of policy writing, unless I am sorely mistaken, is somewhat neglected. Subsequently, many, if not most policies are falling short of the required quality.

This is a sorrowful condition and a serious issue, because a policy communicates a meaning, and meaning demands to be understood. Otherwise, the information security effort can become meaningless. We can hardly afford to neglect this, not just because a policy demonstrates due care and due diligence of management, but because of the significant amount money and effort involved in information security.

I will seek to demonstrate in the pages to come that it is possible to write high quality policy, and what the criteria of such policy are. I would also argue that management should not settle for less than a high quality policy – for their own sake. But first I want to explore the idea of the word policy itself.

Origin and core meaning

The word policy is used in a number of ways to describe different things. This is not necessarily wrong, for every word contains the possibility of multiple meanings and therefore of multiple ideas. The problem, as I can see, arises when those multiple meanings are used interchangeably and indiscriminately. This can create confusion, especially in and beyond the linguistic areas of semiotics, such as pragmatics and perlocution.

It is a matter to be seriously considered. To put it plainly, the communicator must be able to expect the sign he uses in his communication to mean the same for the receiver. If it is not the case, it is questionable whether he can achieve the specific reactions he willed and aimed at with the communication.

You may be inclined to think that I am playing with language. Perhaps I do. But it is no “mere” semiotic pedantry. Definitions are one of the three most potent elements of human language with which we construct a worldview – or even just a “view”. It means that a consensus is built for what a string of syllables put in a particular order might mean. As long as we adhere to the consensus, we are able to understand each other’s thoughts.

Once we start moving away from the consensus, the meaning gets obfuscated. The problem may be stated in the following way. When the perception and representation process of symbols differ between communicator and receiver, the difficulty to construct the world between the two increases and becomes problematic.

Perhaps I can get a bit closer to the point with some examples. The Group Policy in an Active Directory service means something different than a HR Acceptable Usage Policy, and both are quite different from an insurance policy. Others might even use the word policy to describe a legal act or a government regulation. Such liberal use of symbols and signifiers can be daunting even within the same language. Adding to this is the rather unfortunate fact that some use the words policy, procedures, guidelines and so on interchangeably. We so generously tend to assume that everyone sees the world in the same way as we do, irrespective of the obvious differences in the language used, that we do not notice that it is not always the case.

The origin of the word policy can be traced back to ancient Greek. Most of the ancient Greek states were city states (polis = πόλις) with fortifications. Protection was offered behind those fortifications to its citizens (polites = πολΐτης). When someone wanted the protection the city state offered, he had to accept the governing rules applicable to the citizens (politeia = πολιτεία). No acceptance, no protection.

Along the same line, a policy is focused on creating a sense of organisational citizenship amongst staff. Compliance with policy means a good citizen of the organisational city, who therefore is entitled to the benefits of the city. In a sense a policy sets the boundary by laying down the rules that regulate – among many others – how the organisation manages and protects its assets to achieve its objectives.

Leaving etymology aside, yet armed with the knowledge of theoretical linguistics – the relationship of language to reality – which is what semantics studies, we can return to exploring the specific concept of information security policy. I think it justifiable to say that an information security policy is a document that can be considered as a clear statement of management’s intent. In other words, a policy is an important reference document for settling disputes about management’s due diligence.

But this is far from the end of it. A policy can set, inadvertently, the strategic direction, scope, and tone for an organisation’s information security efforts. While it is not operational, it provides consistency from governance to operations. How users operate the controls listed in the policy are detailed in lower level documents, such as standards, procedures, guidelines, and so on. I am probably not being extreme when I say that a policy is losing its usefulness without such additional documents. Therefore, it is recommended to build a complete policy / standards framework, not just a single document.

The hierarchy

In building a policy / standard framework, the first question that needs to be addressed is this: which one has the highest authority? This is an important question, because in case of a dispute over an interpretation the higher authority document should settle the dispute. There are mainly two schools of thought about the hierarchy of information security policies, standards, procedures, etc. These schools of thoughts can be separated by how the policies/standards relationship is viewed.

One school views standards at the top of the hierarchy. This view emphasises that while company information security policies can change as the requirements change, the technology remains relatively constant. Consequently, the appropriate policies are subject to these overarching standards.

The other school of thought places policy above standards. This view considers that the organisation’s requirements drive what technology is going to be used. Therefore, standards are subject to the requirements expressed in the policies. There are certain differences even within this view. Some consider many policies, or even multiple levels of policies. Standards can be even more granulated. The resulting policy/standard hierarchy is very complex, and often complicated.

Others consider a single, overarching policy that is supported by a set of standards. While this hierarchy can be still rather complex, the chance for conflicting authority is reduced. Inherent in all views is the need to find the final authority quickly and effectively.

I will not argue here the wisdom of neither point of view. I found the single policy, multiple standards view the most practical. I will explain this view in detail below.

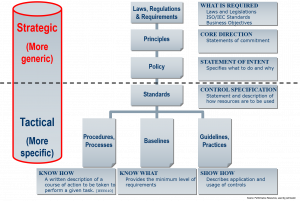

The picture below depicts the policy / standards hierarchy

Principle and policy statements

External variables such as laws and regulations influence the formation of organisational requirements. These are stated as organisational objectives or principles, demonstrating management’s commitment to them. These principles can provide the authoritative directives at each level of the policy hierarchy and can also serve as legal reference points between regulatory, legal and business requirements and security controls. A definition of information security is valuable to be included in this document, as it sets the boundaries of the information security management efforts.

The principle document is usually concise. There can be a dozen principles at most in my view, such as the willingness to comply with the law of the land. Descriptions are usually generic and set the high-level parameters.

The policy expands this by setting the core directions for information security; how management intends to protect the organisation’s information assets. The policy is still generic, but more detailed. All types of controls are considered and listed. It serves as a central point of reference to each document in the hierarchy below it. As this document is the central point of reference, clarity is a necessity.

Standards

One important aspect of this hierarchy is how it changes from strategic to tactical. The switch from strategic to tactical usually happens at the standards. The information security standards describe how available resources shall be used to meet the policy requirements, thus creating specifications for controls. The actual standard statements are still relatively concise, but additional information can be added to them.

The “hows”

The details down to minute level are described in the procedures, guidelines, baselines, etc. This is where even operational issues, such as the “whats” and “hows” are discussed. Baselines provide a minimum set of requirements, providing further details about the required controls. Procedures and practices explain detailed steps or actions to be taken in order to achieve those requirements. Guidelines and processes show the usage of controls and how the intent expressed in the policy can be achieved. Using the different parts of the hierarchy together can then direct and control general operational activities.

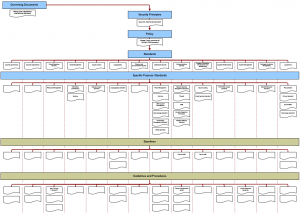

The full hierarchy is shown in the diagram below.

Structural considerations

It is worthwhile to align these documents and the controls they define to the structure of a framework, like the ISO/IEC 27000 family. Such alignment ensures reasonable robustness, while specific local requirements can still be observed. Most importantly though a modular structure can be developed quite easily, resulting in a more transparent hierarchy.

Following the modular structure of the ISO/IEC standards enables easy maintenance, and helps the organisation to ascertain whether their hierarchy is complete or not. When the need arises to a new standard, development is a lot more efficient as the domain the new standard will fall under determines to a degree what the standard will need to contain. Multiple or contradictory standard statements can be avoided. It can also beneficial for the audit process.

Other frameworks can be equally useful to align with, but their particular point of view might limit their usefulness. For the purpose of clarifying my point, this usefulness I refer to here is in the context of policy development. In order for a framework to be useful, it needs to be holistic and covering most aspects of information security to align a policy to it. A more specific framework might be useful for a standard, not for an overall policy.

Expanding the hierarchy

When one probes deeper into the hierarchy, it can be noticed that there are two layers of standards. The higher layer can be considered as generic standards corresponding the domains of the ISO/IEC 27000 family domains. These standards develop further what is contained within the policy by adding the following elements to the standard statement:

- reference to upper level documents

- list of risks addressed

- comments

- reference to lower level documents

The next layer consists “purpose specific standards”. These are addressing a specific area with more details within a given domain. The format of these documents differs from the generic standards, and might even vary from each other. The standard statement is supported by these additional elements:

- brief justification for the standard statement

- short comments on the intent and best practice

- key performance indicators

- tips and warnings

- reference to related documents

Having these additional elements means that a standard statement takes up one page at each layer. In this connection I must note that the operative, and therefore mandatory part is the standard statement. The rest is only commentary. Aptly formed statements combined with the additional elements can make the intent unambiguous.

A small example here might clarify what I mean by the word hierarchy. Perimeter defence for example is first addressed at the information security principles which states among other statements that

“<organisation> information security measures will ensure that the integrity of its information, assets and systems can be relied on to meet the business needs.”

A more detailed statement is contained within the information security policy

“The <organisation> logical domains shall have clearly defined perimeters and shall be protected from unauthorised access.”

A more specific statement is provided in the Communications Security Standard, stating that

“Network devices shall be hardened against compromise prior to deployment.”

This standard makes direct references to the Firewall Standard, that states

“Firewall rules shall be based on authorised and documented business requirements.”

Other standards provide support to these statements and objectives. Further details can be found in the Firewall SOE baselines. These baselines would be referenced both from the standards and policy (positioned in a higher position of the hierarchy) as well as from the Firewall Configuration Guide (positioned at the same level or lower in the hierarchy.

Language usage

Coming back to linguistics, some attention must obviously be given to the style and tone of the language as the change from strategic to tactical is also noticeable by the language used. A policy statement is formal. The word “shall” and “shall not” is to be used. It is important not for style or for the glamour of language necessarily, but for the intended significance and force of a statement. It indicates that disobeying the policy statement has enforceable consequences.

Standards still can use “shall” and “shall not”. However, often it is more practical to use “must” and “must not”, or even a structure of “to be”. See the previous paragraph for such an example. In this connection, I must note that “must” and “has to” differ in terms of the source of obligation and a considered choice needs to be made which one to use.

Procedures and other tactical documents use words like “should”, “should not”, “can”, “may”, “may not” and so on. They indicate that the force of the statement is to be considered, but is not necessarily mandatory. They convey the meaning of “recommended” or “optional”, with the connotation that in particular circumstances they even can be ignored. However, before such decision is made, the full implications of the choice and the resulting action need to be explored. Even in a situation like that an alternative action is the wisest choice.

It may be of some interest to note, in this connection, that the audience at each level of the hierarchy differs greatly, and the development of the hierarchy needs to carefully consider it. In addition to this and more importantly authors are different as well. We must remember that a policy is written for an audience on behalf of senior management. It is highly unlikely that a CEO would write the policy. He signs it off. The point to be stressed here is that the purpose and will of the approver has to be kept intact by the actual writer so the reception of the communication will be based on the same purpose. Otherwise there will be little if not no will to fulfil that purpose.

I have mentioned all of this because I feel it necessary to labour the point that the language used influences the interpretation of these documents. Since the principles, the policy and the standards communicate the intent and the commitment of management, they have to be conveyed to the rest of the organisation in a clear and concise manner. The statements therefore need to be as clear and unambiguous as possible. What it comes down to is this: the aim is to have one possible interpretation only.

I am well aware, of course, that no one can stop anyone from misreading anything or rationalising anything or excusing anything. Yet the opportunity to yield to such temptation needs to be curtailed as much as possible. I shall not speak here of what may happen if it is not.

Finally, it remains to be said that the operative parts (statements) in these documents are expected to be implemented as stated. Yet, they have to be considered in the spirit of the law compared to the letter of the law. That’s why the language used is so important.

Summary

In spite of the dogmatic tone I have taken in stating it, the policy standard hierarchy is offered only as an example of how I think they can be written to full effect. I aimed to highlight the intricacies of the document writing tradecraft that ensures the provision a coherent framework from information security governance through management to operations. It is necessary for me to say at once that there are some talented policy writers, but they are almost endangered species. Admittedly, this last observation, as well as some that preceded it, should be regarded as conjectures. But what if they are not?

HI Endre,

That’s a long post! One aspect missing is the audience – or rather audiences, for there are several. A lot of the policy-related issues I see in practice stem from this.

For example, policies tell workers what management expects them to do/not do (hence “workers” are one audience) and tell the lawyers what employees were required to do/not do (so the lawyers and courts are another audience). The language that works for one doesn’t work for the other. Multiply that by the number of audiences and we face a complex problem,

Thanks Gary,

You raise a very good point.

However, I am not sure to what extent a writer needs to consider other audiences beyond the main one; the employees. I suggest the well thought out illocutionary acts would cater for the rest.

Hello again Endre.

Even “employees” is a group within which we could identify number of audiences – consider staff and management, for instance, or newcomers and long-time employees. People differ in IQ, reading ability, interests, experience, competence and so forth. Some of us enjoy the written word and are happy to read and consider even lengthy pieces and obscure words (such as “illocutionary” – I had to look that one up!), while others prefer more succinct outlines or diagrams. Some people skim-read everything (at best!), and a few reactionaries actively look for loopholes and other issues in the wording that leave them free to do whatever they want or simply resist/challenge authority. Some don’t appreciate being told stuff at all: they prefer to be shown, or even to figure stuff out for themselves from first principles before accepting and internalising it. Most of us need time to read, consider and absorb stuff (especially complex, obscure or difficult stuff): the amount of time varies between individuals, and topics, and circumstances (e.g. if someone is maxed-out with other activities, they won’t pay much attention to new policies). Some people pick things up instantly in one pass, others need to be reminded, or to talk it over with others.

Maybe I’m over-complicating matters but I believe there are several reasons why developing, communicating and implementing effective policies is tough in practice, tougher than it might appear.

I agree Gary,

Policy writing – to a certain degree – is a form of art.

I don’t think you over-complicate the matter, but I would argue that what you are talking about is more in the jurisdiction of policy management (including dissemination, training, enforcement, etc.) than in the jurisdiction of the actual policy writing. Having said that, I agree again, it is a vast area, and worth to explore.

Folks,

Gary has produced extensive material in this particular area, check it out!

Thanks Endre.

I was mostly thinking/talking about writing policies, but you are correct: that is just one part of policy management. We could elaborate on the policy lifecycle, for instance, and how to go about planning a coherent suite of infosec policies that hangs together AND complements various other corporate policies.

“Information Security Policies, Procedures, and Standards” by Thomas R. Peltier (published by Auerbach) offers sound advice – a substantial, well-written textbook on writing infosec policies!

If that’s too much, we’ve published an infosec policy FAQ on our website (www.noticebored.com/html/existingfaq.html) and I blog about policies from time to time at blog.NoticeBored.com

Kind regards,

Gary (Gary@isect.com)